| INDEX | 1300-1599 | 1600s | 1700s | 1800s | 1900s | CROSS-ERA | ETHNO | |

| MISCELLANY | CONTACT | SEARCH | |

A corset is a close-fitting piece of clothing that has been stiffened by various

means in order to shape a woman's (also a man's, but rarely) torso to conform

to the fashionable silhouette of the time. The term "corset" only

came into use during the 19th century; before that, such a garment was usually

referred to as a pair of bodies, a stiff bodice, a pair of stays or, simply,

stays. In French 18th century texts (e.g. Garsault, Diderot), you can find the

term corset as referring to a lightly stiffened bodice with tie-on sleeves,

whereas proper stays are called corps.

|

1660s stays with sleeves |

The origins of the corset are unknown. From the early 16th century, corset-shaped cages of iron are preserved*, but it's almost certain that they had nothing to do with normal clothing. Theories run from early fetish accessories to brute attempts at orthopaedics. Judging from contemporary depictions, stiffened bodices must have been worn around 1530 because the straight, conical line of the torso seen e.g. in portaits of Venetian ladies or Eleanora di Toledo could not have been achieved otherwise. The neckline is relatively high and the chest pressed flat rather than pushed up.

Very few stays from the 16th and 17th century have been preserved. This may be due to the fact that until well into the 17th century, the bodice of the dress itself was stiffened so that an extra corset was unnecessary. Only towards the end of the 17th century, the shaping stays finally became a piece of cothing in its own right, independent from the dress bodice. From now on, ladies dressed not in a combination of skirt and stiff bodice, but in a combination of skirt and jacket or skirt and robe worn over a stiff bodice that had been demoted to underwear.

Link: 1640s stays at the Manchester Galleries

|

|

|

1770s stays |

In the 18th century, stays are definitely underwear. Only in case of the Robe à l'Allemande, the stiff bodice survived until about 1730, in case of the French court robe even longer. The shape of stays is not much different from that of the 17th century: Conical, pressing the breast up and together, with tabs over the hips. The tabs are formed by cuts from the lower edge up to the waistline that spread when the stays are worn, giving the hips room. They prevent the waistband of the skirt from crawling under the stays, and the waistline of the stays from digging into the flesh.

There are stays that lace at the back (Diderot calls them corps fermé, closed stays) and those that lace across a stiff stomacher in front (corps ouvert, or open stays). Examples that lace both back and front (but not over a stomacher) are quite rare. Stays that lace in front only are even rarer and so far only known to me from the region of Southern Germany. In all these cases, spiral lacing is used.

Although 18th century stays were not meant to be seen, they are often quite decorative, with finely stitched tunnels for the boning, precious silk brocade and possibly gold trim. The inside, on the other hand, usually looks downright sloppy, even in outwardly fine stays.

The basic shape of stays didn't change the whole century long. Towards the end, around 1790, when dress waists begin to wander upwards, the stays become slightly shorter. Since paniers were not worn anymore, the skirt is supported by small pads sewn to the tabs. At the same time, physicians make themselves heard, warning against the harm done by tight-lacing. While lacing wasn't usually overdone as much as one century later, it often started earlier: It started with tightly wrapping babies and included children's corsets, forcing the still soft skeleton into a fashionable shape.

From 1794, the waist moved higher and arrived just under the bust around 1796. A new kind of corset is needed: The torso, hidden under flowing muslin, doesn't need shaping anymore. The breasts still need lifting, but they're supposed to stay apart. To achieve this, cups are employed for the first time. The busk, which in the 17th century had served to keep the front of the stays straight, now came back into use to keep the cups apart. The shape follows the natural form of the body and widens over the hips by means of triangular inserts.

Since slender figures could keep the bust in shape with the help of only a firm bodice lining, it is mainly stout and over-endowed ones who wear corsets or short stays which already looked like early bras. Therefore, not many corsets from that time have been preserved. Unlike the earlier ones, they tend to be plain and functional. Maybe the fact that they contained less boning led people to refer to them by the (French) term for lightly boned bodices, corset. This is just a theory, but it would explain why the earlier term corps/stays had been replaced with corset by the 1820s.

|

|

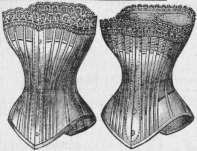

Corsets of 1890 |

When the waist moves back to its natural place during the 1820s, corsets become more popular again. Until the 1840s, well-shaped figures can do without one without drawing Looks. In 1828, lacing eyelets with hammered-in metal grommets are invented (until then, eyelets had been stitched). A year later, the planchet came in: Two metal strips, one with little mushroom-shaped heads, the other with eyelets, used to close and open the corset in front without having to undo the lacing every time. This busk, as it is called in English, makes it possible to change the lacing completely: Both ends of the cord are threaded through the eyelets crosswise and knotted together at the end. At waist level, one loop is formed on either side and used to pull the lacing tight. This kind of lacing is still used today.

Around the middle of the century, corsets become mandatory again. The shape is already the famous hourglass that we associate with corsets today. While tailors still experiment with complex, strange and unusual patterns – the shape is still relatively new, after all – the look stays rather plain. From about 1860, when some patterns have caught on, more emphasis is placed on beautiful fabrics and elegant lines again. From the years around 1870-90, a large number of meticulously made corsets has been preserved, partially embroidered and with satin top fabric in various of colours.

Until c. 1870, the crinoline hid anything from the waist down, so corsets ended not much below the waist. Later, dresses closely hug the figure at least in front, so corsets become longer. This development reached a peak around 1880, when the fashionable silhouette hugged the hips on all sides. The belly is tamed, but not flattened, by a new kind of busk: The pear-shaped spoon busk (see right corset in the picture above) bends inwards to compress the stomach region, then outwards over the belly, an in again over the lower abdomen. If laced tightly, a spoon busk forces the soft bits (i.e. fat as well as inner organs) downwards – and during the 1890s, tight-lacing becomes so popular that physicians sound the alarm again.

|

|

S-line corset, 1902 |

Their warnings were heard and a new shape of corset was invented. With its straight front, it was supposed to take pressure away from the stomach region. It ended just below the breasts to give them room. However, fashion didn't just accept the new shape, but exaggerated it so that the busk pressed the belly and hips backwards and forced the wearer into a hollow-backed posture, the so-called straight-front or S-line.

This unnatural posture makes the originally well-meant corset even more uncomfortable and harmful than any before, causing much damage to the musculoskeletal system. It reaches way down around the hips and for the first time and has long elastic strips sewn to the lower edge with clips on the end to hold the stockings up. Since there still is a long shift between the corset and the stockings, the shift must be pulled and bunched up to fasten the clips to the stockings – yet another source of discomfort that may have led to the demise of first the shift, then the corset.

|

|

1914 corset |

The rise of women's lib, the rational dress movement and progressive designers such as Poiret saw to it that this fashion did not prevail for long: Even before the beginning of WWI, the corset has begun its downslide. Fashion now permits women to wear elegant dresses without a corset. Nevertheless, corsets were still worn for a few years more, but both the S-line and tight-lacing disappear. Elastic inserts give more room for movement – and they have to, because post-1910 corsets reach so far down that they would otherwise prevent the wearer from sitting and walking. The so-called war crinoline (1915/16) with its high waists and flared skirts made even those unnecessary.

|

|

Gidled and bra, 1939 |

One could say that the corsets slid downwards and became more elastic. The straight, waist-less Garçonne fashion of the 1920s favoured only lightly stiffened hip girdles partly made of elastic. They were not supposed to constrict the waist, but to control the belly and hips. The chest was supported (and, if necessary, reduced to a boyish look) by a bra. Girdle and bra persevered through the 30s and 40s as well.

It was Dior's "New Style" that put the waist back onto centre stage.

His models emphasise an extremely small waist and wide hips, so that corsets,

or at least a watered-down version of them, see a short-lived renaissance. In

the 1950s, elastic girdles without any boning come back, only to be washed away

by the flower-power 60s and 70s.

Corsets have probably been worn for erotic purposes during all that time, even while they had been gone from fashion. Only in the 1980s, Madonna brought them back into public attention with the help of her favourite designer, Gaultier – as top garment. Her version, however, was more like a tight bodice than a proper corset. Nowadays, real corsets are only rarely worn. Sometimes a celebrity or lover of historical fashion may wear it visibly as a fashion statement, but mostly, it still is worn underneath for erotic reasons. Whether they be waist-cinchers, under-bust, half-bust or full-bust: The basic shape is still the same as 1860-80, only that they usually don't compress the waist nearly as much.

Sometimes even apparently trustworthy sources spread wrong or at least highly doubtful statements about corsets. Some of them are based on wrong interpretations of contemporary sources, some on contemporary sources that exaggerate for some reason.

Most legends of course are about impossibly small waists. The "oldest" and most extreme one is the one that asserts that Katerina de' Medici, Queen of France in the late 16th century, required her ladies-in-waiting to have 13 inch waists. Someone who doesn't use inches in everyday life will first try to convert that into centimetres and then start to wonder which inch they should use since there were so many different units of that name. Someone must have written about it in Katerina's time – which inch did they use? Did the author (19th century, I think) that spread this legend know or even think about the fact that there were different inches about? Did they convert them to modern inches, and if yes: To which one? And did they have proper information about how long a contemporary inch was? That's a lot of questions already. And the 19th century author may well have invented it all, because as far as I know, no contemporary source for the statement has been found. Well, let's just say we're talking about 13 British Imperial inches. Even the most extreme modern-day exponent of tight-lacing, Cathy Jung, only manages 15 Imperial inches in an hourglass corset. With a 16th century conical corset, this would be impossible even if one takes into consideration that women used to be smaller then.

The waist of Empress Sisi of Austria is sometimes given as 40 cm, sometimes as 47, and even as 50 cm. That variance alone should engender doubt. However, it is well known that she was a victim of her own vanity.

Some early photographs show women – mostly actresses – with extreme waists. In some cases, the rigid, artificial-looking posture shows that this was not their normal state, i.e. maybe they laced especially tightly just for the photo. Retouching was used extensively in those days and brought forth masters of the art. Porn photographs of the time show naked women who would not be considered slender by modern standards. Patterns of the 1880s quote waist measurements of 58-64 cm, those of the 1890s (the height of tight-lacing) 54-60 cm. With an average height of 160 cm, this seems realistic.

Sometimes you find quotes from late 19th century magazines reporting that a lady died after having taken a fall in the street. A broken rib was pressed inwards by the tightly laced corset, causing it to puncture a lung or the liver. I have even seen a contemporary magazine which reported the story and therefore believed it – until I fould the same story, slightly altered, quoted from a different magazine, from a different year. I am now convinced that we're dealing with an urban legend.

Another urban legend says that some fashion victims had their lower rib removed so that they might achieve a smaller waist. In the late 19th century, when some doctors refused to believe that lethal illnesses could be caused by creatures too small to see and therefore didn't see why they should wash their hand before surgery. The survival rate was low enough that surgery was the last resort, so why should anyone undergo it unless their life was at stake?

Waugh, Nora. Corsets and Crinolines. New York: Routledge, 1996.

Fontanel, Béatrice: Support and Seduction: A history of corsets and

bras. New York: Harry N. Adams, 1997.

Junker, Almut, und Eva Stille. Dessous : Zur Geschichte der Unterwäsche

1700-1960. Frankfurt: Historisches Museum, 1991

*) In fact, I sometimes wonder whether those items are fakes, just like some chastity belts that turned out, after decades of unquestioned existence in museums, to be 19th century artifacts. The Victorians liked to push clichés about earlier, oh-so-primitive eras.

Content, layout and images of this page

and any sub-page of the domains marquise.de, contouche.de, lumieres.de, manteau.de and costumebase.org are copyright (c) 1997-2022 by Alexa Bender. All rights reserved. See Copyright Page. GDPO

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.